UX lessons from the very intentional design of IKEA (Part 1)

How putting together furniture can help you think about user onboarding and retention.

"How am I supposed to take this home now?" I grumbled as I struggled to find a taxi, cradling a few bags and boxes in my arms. "Then why'd you buy it now?" my partner asked.

Why, indeed, did I buy it now, I wondered.

I'd gone in to buy a chef's knife. Somehow, I also ended with a French press, a 45W LED bulb, a few meal containers, and sealing clips.

So being the obsessive nerd that I am, I went into analysis mode of the neuro-design. How did I, someone who designs for behaviours, get tricked into doing something?

So this is not going to be another rehash of how IKEA's e-commerce experience can be redesigned. That's for two main reasons —

- UX isn't just about screens, and we need to be more cognizant of that;

- It has been done to death, and I doubt I'll be able to add much additional value by rehashing that conversation.

So what in the world am I going on about?

The meme

I'm sure you've seen some or the other variation of this meme. By all accounts, the IKEA product experience is frustrating and would be, at face value, considered overall terrible.

And yet, you'll at least know someone who knows someone who WON'T part with her KLAGSHAMN sofa-bed. The damn thing would have had its upholstery and various other parts replaced more times than the guy behind you honks the second the signal turns green. At this point, it would have been more cost-effective to just buy a new one. By all means, irrational behaviour, right?

So, what gives?

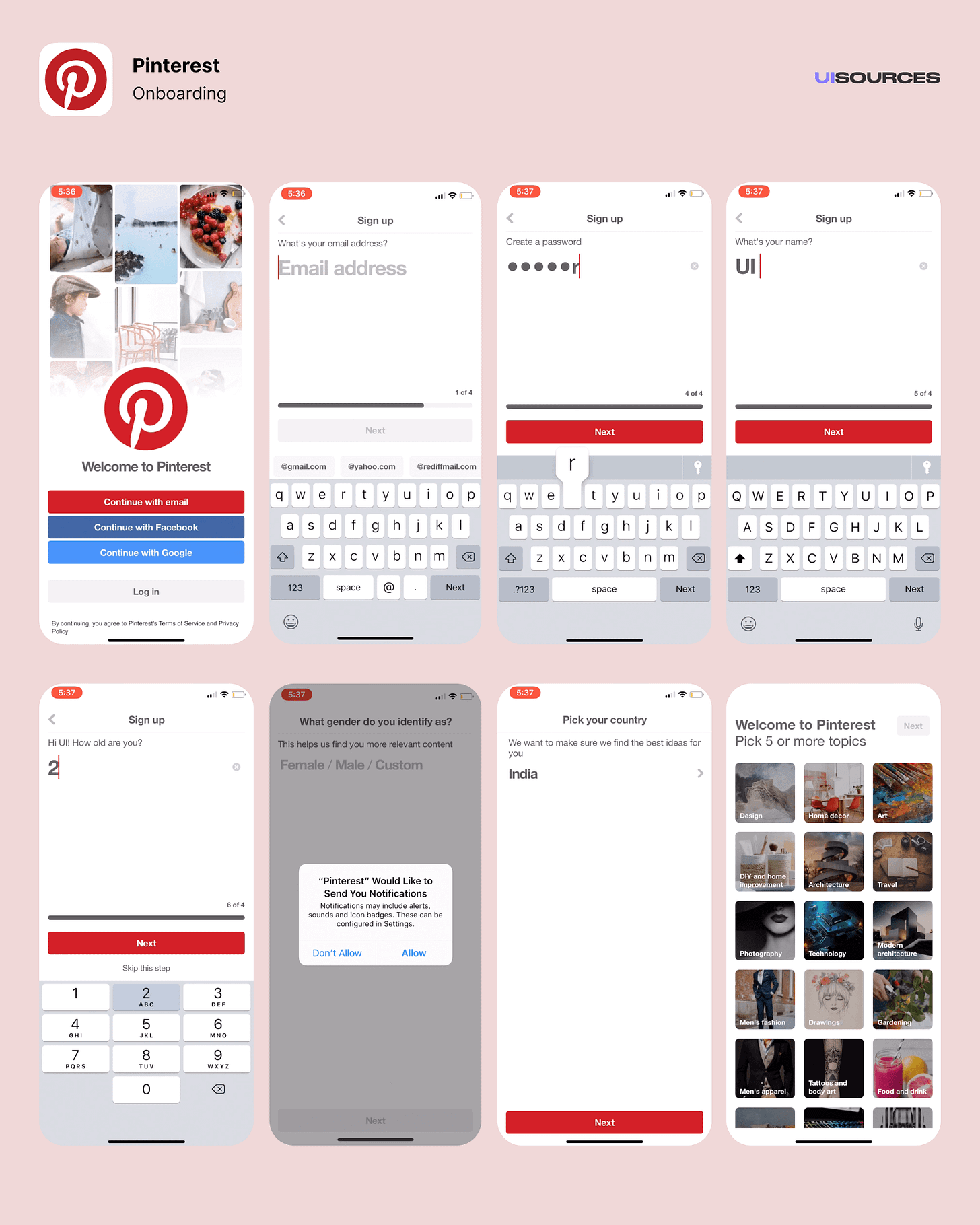

Let's look at Pinterest.

When you sign up for a Pinterest account, you first go through a series of steps in an onboarding form, which asks you to provide a number of inputs to customise your homepage. Once you do this, the app lands you on “your“ homepage, allowing you to start seeing ‘pins’.

Over a period of time, it also prompts you as you scroll and view various pins to "like" items you would like to see more of.

If you go by conventional wisdom, Pinterest is committing at least 2 cardinal sins:

- It is not allowing the user to get to the value offering (the content in this case) of the app ASAP.

- It is interrupting a user flow to seek input the user doesn't really need to give.

So why does Pinterest's phenomenal success fly in the face of this conventional wisdom?

The IKEA Effect

No, I'm not making that term up. This is in fact a documented phenomena. Business psychologist Michael Norton and his colleagues Daniel Mochon and Dan Ariely dubbed it the "IKEA Effect".

In a nutshell, the IKEA effect says that we tend to like things more if we’ve invested effort to create them.

In this study, where participants folded origami cranes and frogs, assembled IKEA boxes, and built sets of LEGO, and then bid on their creations as well as others’, this bias led people to overestimate the value of their work so much that they believed their origami was only slightly less valuable than origami folded by an expert.1

This also forms the basis23 for the "little bit of work" aspect of the Hook Model Canvas in Nir Eyal's Hooked4, which gets into more detail on this topic. An absolute must-read for any UX/product designer.

“[...] labor leads to love only when that labor is successful.”

- Norton, Mochon, & Ariely, 2012

When people had failed in their attempts to fold paper cranes and construct Lego sets, the IKEA effect weakened — as it also did when they were forced to dismantle their creations.

I bought that French press I mentioned earlier because I usually prefer the coffee I make myself, even when it's objectively mediocre. So I was willing to make the investments required to make it myself, grounds and all.

My partner and I like to cook a little “experimentally" at times. Even in instances where the end result is only borderline edible, we like it. Because we made it together.

Is it cheaper than just ordering in pasta? Hell, no.

Did we care? Hell, no.

The case for intentional friction

Why does this seemingly counter-intuitive phenomena work so effectively for businesses looking to encourage repeated long-term use of their products? Let's take a look.

We want to feel like our effort was worth it

Think about this for a moment. You've already taken the effort to set up Pinterest to your liking. As you continue using the app, the app gets smarter, showing you more of the content that you want to see, with less and less effort every time, to the point of being almost telepathic.

So what incentive would you have to leave the app, or switch to a competitor? It would have to be a hell of an incentive.

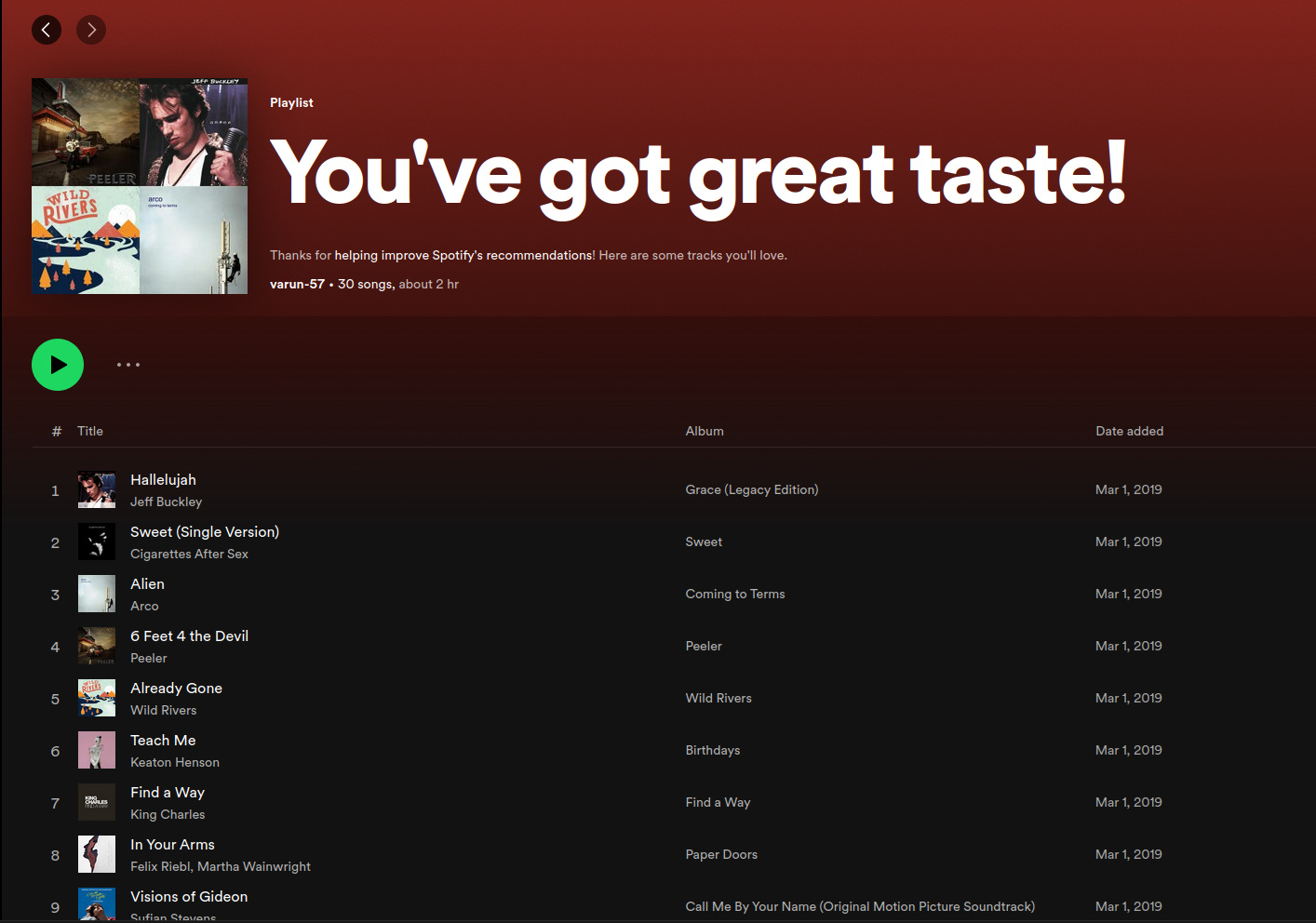

If you already use Spotify, you know exactly what I'm talking about. Why would you want to most to YouTube Music or Apple Music?

Spotify makes it clear that your 'Discover Weekly' and 'Your Daily Mix' is created based on which songs you listen to.

We have a psychological need to feel competent

When instant cake mixes were introduced in America by P. Duff and Sons in the 1950s, American housewives were initially wary. These boxes of dehydrated powder promised to make baking cakes easy — and they did. Almost too easy.

The manufacturers discovered that requiring the extra step of adding an egg introduced just enough effort in the process to make the housewives satisfied with their work. To feel they had indeed “baked the cake”, and not cheated. Of course, adding egg to a cake does make it 10x better (don't @ me). But the greater sense of accomplishment gained from a little extra labor is believed to have been essential to the phenomenal success of the cake mix5.

When we do DIY activities like assembling a piece of furniture or baking a cake, it boosts our sense of self-efficacy. Not only does this sense of accomplishment feel good in the moment, it fulfills a deep psychological need. This is partially why we see items that we put together ourselves as so much more valuable than they actually are.

Why is this important?

You may have noticed that “do-it-yourself” products seem to have been on the rise recently. Half the YouTubers I watch are either promoting Blue Apron or Hello Fresh. These meal kit delivery services, where subscribers receive a weekly box of pre-portioned ingredients so they can whip up home-cooked meals, are just one example. This industry is expected to hit a value of $20 billion by 2027.6

Interestingly enough, there products are actually more expensive7 than just buying groceries and cooking them.

The IKEA effect can reel us into products like these, by making us feel like the work we put into something made it worth its higher actual cost.

"I've built it, therefore it'll last".

- Probably everyone

On top of this, many companies that capitalize on the IKEA effect (such as IKEA itself) have reputations for being affordable or cost-effective. Through this bias, brands get to have their cake and eat it too: customers do most of the work, feel happy about it, and come away with the perception that they got a good deal.8

How can you apply this?

Yeah, I tend to go on for a bit about something before getting to the good stuff. Working on that.

Make your users do "a little bit of work"

Identify opportunities in your product where you can introduce the requirement for some investment on the user's part in setting up their experience. This can take a number of forms:

- Seek relevant user inputs during onboarding to meaningfully customise the experience ahead.

- Refer to the Pinterest example above.

- Encourage "power usage" of your product to adapt to unique user wants

- Once you've set up Gmail with your labels, rules, filters, etc., there's a massive inconvenience barrier discouraging you to switch to a competitor, since you'd have to repeat all that effort.

- Create opportunities for users to take ownership of their experience.

- Spotify makes it clear that your 'Discover Weekly' and 'Your Daily Mix' is created based on which songs you listen to.

Be ready to kill your babies

Apart from our decisions about coffee tables and meal kits, the IKEA effect could potentially lead us to overvalue in our own work.9

When we’ve put our blood, sweat, and tears into a project, we can get blinded to issues or places where there’s room for improvement. It's very easy to get stuck in the trap of justifying the effort, not wanting to feel inept, or just plain overconfidence. The end result is an output that's not the best we're capable of.

Just because you’ve made something yourself, doesn’t necessarily mean it can’t be better.

Conclusion

What has been your IKEA effect story? Share it down below in the comments!

TL;DR

- Users put more value on products they have invested effort in.

- Identify opportunities in your product where you can introduce the requirement for some investment on the user's part in setting up their experience.

- Don't allow the IKEA effect to make you biased towards your own work.